Following last month’s webinar on the broad concept of ‘bitemporality’—now available on-demand here—we have written-up some of the excellent audience Q&A below. Note: XTDB is a bitemporal database product by JUXT for solving complex problems with dynamic and time-related data.

We have also since released a new JUXT Cast episode where we interviewed Kent Beck prompted by his recent series of articles and examples that briefly featured in the webinar.

Principled infinity?

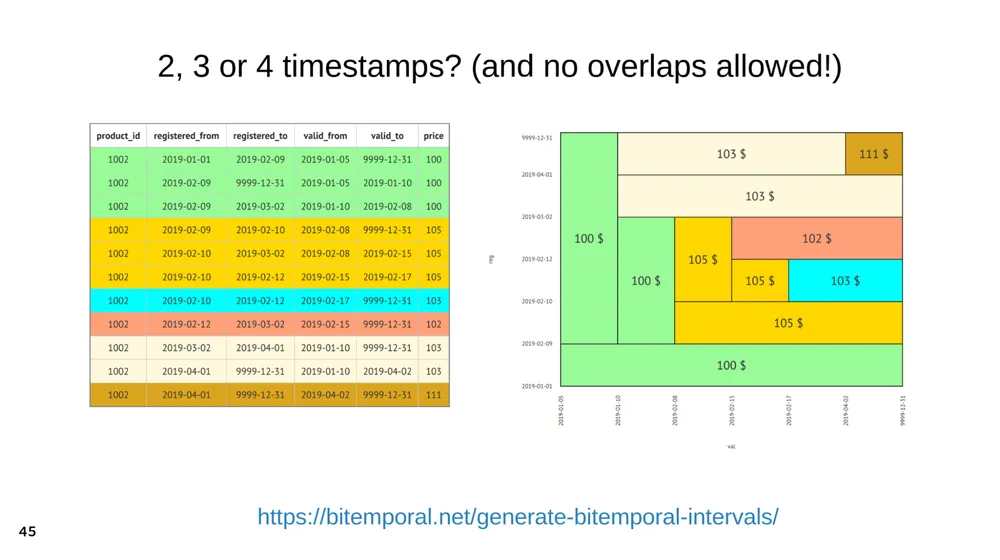

9999-12-31 / ‘Infinity’ / ∞ / “until changed”

Question: In various examples shown infinity was modelled as a very large date, e.g. ‘9999-12-31’, however in some domains you might want to model much further into the future (for example in a simulation or game). Does XTDB have a principled model of infinity with an explicit sentinel value? Or does it also use that same kind of MAX_DATE style valid-to?

James: XTDB does use a principled model of infinity and takes inspiration from Postgres, which allows ‘null’ on either end of an interval to mean ‘unbounded’. In a previous life before working on XTDB I’ve seen cases where we’ve had to work with, for example, MySQL’s ‘0000-00-00’ date meaning “the start of time”, and I’m sure most people will have seen user-facing UIs where those kinds of special dates have leaked out. This is definitely an area of complexity that we hope to simplify for users.

Temporality in practice?

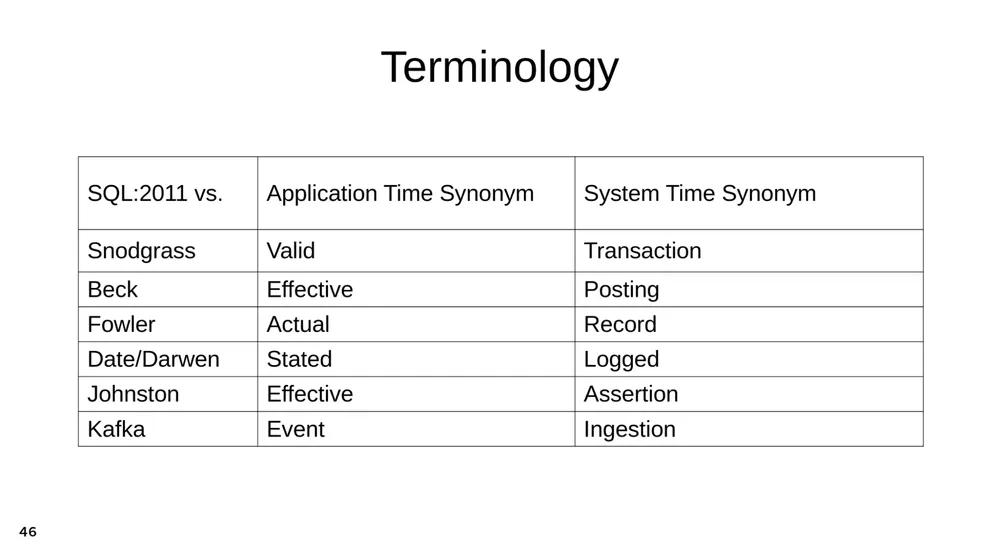

Naming is hard. Agreeing names is harder.

Question: Thinking about the slide where you showed the terms used by various systems, including Kafka - I wonder if you can compare and contrast how the main modern systems handle temporality and bitemporality.

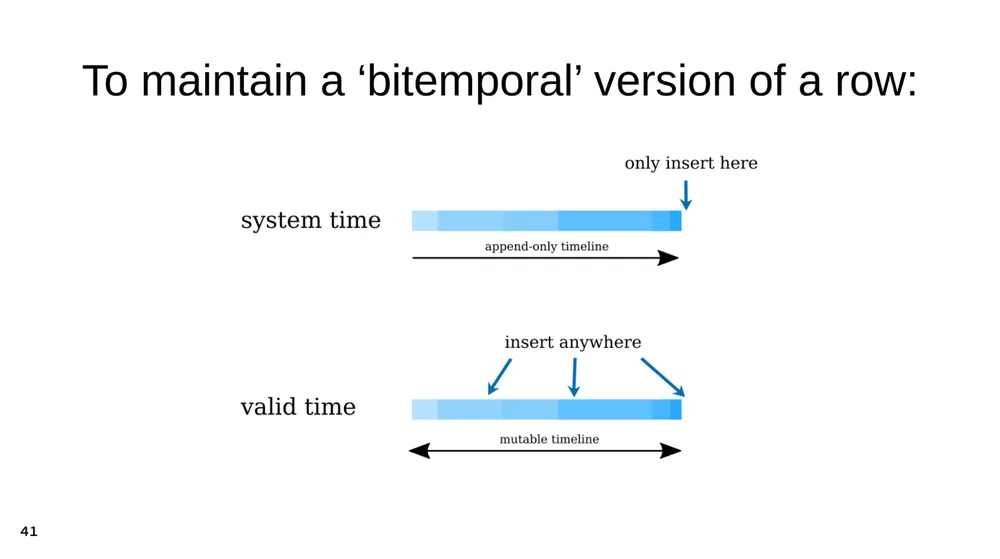

Jeremy: An increasing number of modern systems are offering some form of ‘unitemporal’ time-travel facilities for querying historic snapshots of databases at earlier points in system time (potentially even against a forking model of system time defined by a SHA). This is at least a clear improvement over regular ‘atemporal’ databases, but in these systems you are unable to correct previous data or make any out-of-order adjustments, meaning you cannot really expose these capabilities in your application model. System time is still very useful for auditing, debugging and deriving new data from a stable basis, but is often insufficient for typical ‘time-travel’ business requirements.

On bitemporality specifically, I don’t think anything particularly noteworthy has changed since this Survey of SQL:2011 Temporal Features blog post was written in 2019. The four main databases discussed there are still in the top-10 of popular databases - so the state of the art isn’t completely lacking, but there are undoubtedly some big caveats to how you use these bitemporal features. For example it requires a lot of expertise and forethought to think “is this the right time to use this database feature”.

Of course if your database doesn’t support any notion of system time or valid time then you’re going to end up implementing these concepts in userspace, which is doable as we’ve seen, but it is something you need to make sure you implement correctly and properly budget time for.

While developing XTDB over the last 5 years we’ve really taken efforts to make bitemporality as easy to think about as possible. But even from day one it’s always been a case of simply being able to put in documents and then when you pull out those documents again you can see all the various timestamps that the system is maintaining for you automatically.

In XTDB you actually don’t have to think about bitemporality until you actually need to use it, whereas all these other systems force you to consider how bitemporality fits into your schema upfront. And this upfront, manual design effort can really affect how ordinary features like primary keys and foreign keys work, not to mention schema changes.

In summary, I don’t see existing database technologies ever truly solving this entire space of temporality particularly well. And as a consequence it means people don’t routinely embrace the features and possibilities on offer, which then means vendors don’t bother to invest much energy in making the experience any better.

James: I would add that broadly speaking XTDB does follow the semantics of SQL:2011 and this is largely so that we maintain compatibility with other tools and databases that do support temporal tables. But there’s one area in particular where we’ve made a really conscious decision to deviate from the specification, and that is in the area of valid time.

In the specification the default behaviour is that queries and transactions apply for all valid time. However, we prefer that XTDB behaves as closely as possible to a traditional update-in-place database. Therefore our transaction semantics instead default to as-of-now in valid time, so that when you put in a new version of a record its validity defaults to as-of-now until the end-of-time. And this essentially means that developers can keep all of their existing atemporal queries as they are, but then they can incrementally add bitemporal queries as & when they need them.

In contrast to our greenfield work on XTDB, the SQL:2011 design had a lot of backwards compatibility constraints to consider—in keeping with existing userspace implementations on established database products—and therefore things behave more like regular tables with some extra built-in automation. We’re choosing to deviate from that aspect of the specification to make the default developer experience much more ergonomic.

How is uniqueness handled?

Bitemporal tables are just like normal tables…with various extra columns, constraints, and update logic.

Question: How would a constraint like UNIQUE work? Does the data have to be unique over all time? Or just at the time of writing? And would changing historical data violate that newly added constraint?

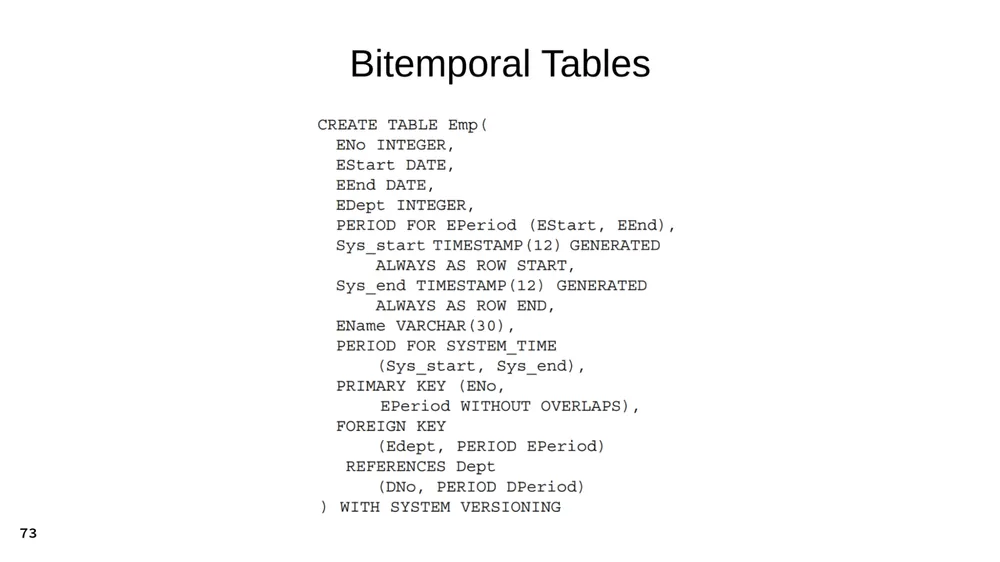

Jeremy: Regular UNIQUE constraints would, by default, apply to all temporal tables just as they would to normal tables that happen to have a few arbitrary timestamp columns - there are no special rules. This means UNIQUE implies unique over all time, and therefore attempting to change historical data could easily violate a newly added constraint.

James: A key addition for SQL:2011 bitemporal table schema is to change the primary key unique constraint ever so slightly. This unique constraint now covers your existing primary key and your valid time period “WITHOUT OVERLAPS”, which is a SQL:2011 construct.

Schema evolution?

SQL’s “Data Definition Language” doesn’t keep track of schema versions - but what if it did?

Question: How does schema evolution work with bitemporal tables? Does XTDB provide any support for schema evolution?

Jeremy: Across the various existing implementations out there of bitemporal tables we’ve found that application developers are expected to temporarily remove all temporal constraints before they can apply their regular database schema changes, and then the constraints must be manually re-applied. Not only does this make regular schema management operations more complicated but it also doesn’t address the subsequent problem (and typical requirement) of how to maintain consistent access to data as it appeared in older versions of tables. This all detracts from the otherwise ‘immutable’ qualities of the functionality.

In contrast XTDB at its core is schema-less meaning it doesn’t assume any knowledge of column types or what columns exist. Instead it tracks these things incrementally so that you don’t have to tell the database in advance how you’re going to use it. Of course, there’s a trade-off here, because you still have to model the schema somewhere. In the coming months we’d like to add more incremental schema features, to allow users to lock down exactly what you can or can’t put into a table.

Being schema-less at its core also means that XTDB defers many of the problems that come with trying to directly integrate temporality and the standard SQL schema model, because really the schema itself also needs to be treated as a set of temporal records. Whilst your application will inevitably have a schema at some point and that does need to live somewhere in the database, we believe it’s important for us to build the underlying database system in layers such that schema management exists as a discrete layer on top. This will allow more control for applications to rigorously establish their own temporal model of schema.

Is this Event Sourcing?

An append-only data model with system time ordering…looks remarkably similar to an “event store”.

Question: This seems like it shares a lot of the aims of Event Sourcing - particularly, the audit trail and history requirements. Can the two work together, or do you have to pick one or the other?

Jeremy: Event Sourcing and related notions of Domain Driven Design point to an alternative view on the nature of auditable record keeping and software architecture that rejects the traditional role of SQL databases as the primary source of truth.

Systems built following these patterns will often use update-in-place SQL databases as part of their design anyway and temporal tables arguably make the case for building on top of SQL even stronger. For example, bitemporal tables could be used to address various time-travel requirements within complex ‘aggregates’ or ‘projections’, or for providing facilities to simplify event processing.

It’s a big area of discussion with room for many integration possibilities, and seems to be broadly uncharted in practice.

Bonus question on XTDB, SQL and Datalog

Question: Can applications use XTDB’s Datalog and SQL APIs interchangeably, and without any need for Clojure?

James: Yes, absolutely. This is exactly one of the things that we wanted to achieve with the XTDB 2.x design. All of the data that Jeremy has been showing in the examples here can be queried both from SQL and from an edn-based Datalog API that is similar to the Datalog query API of XTDB 1.x. For example you can insert data as SQL and then query it back using Datalog, and vice versa you can insert the data using Datalog and query it with SQL.

We’ve always been conscious that in many companies you might get some developers who are swayed by the qualities of Datalog and the productivity gains it can bring, but you can’t ignore (1) the enormous ecosystem behind SQL, and (2) the wealth of combined decades of people’s experience. So bringing these worlds and their combined potential together is really something we have been striving for.

That’s a wrap!

We hope you have found this transcript insightful. Be sure to check out the webinar and other links for more information and discussion. Finally, the XTDB team is always interested to hear from practitioners and people working in this space - please do get in touch: hello@xtdb.com