Events, and the patterns based on them, have transformed our approach to architecture and system design. There are lots of terms used in the day-to-day discussion of Event Driven Architecture (EDA): Event Sourcing (ES), Command Sourcing (CS), Command Query Separation (CQS), Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS), Event, Domain Event, Command, Message, Projection, State, Eventual Consistency, Read Model, Write Model, Logs, Hydration, Aggregation, Replay, Orchestration, Choreography …and so on. This is just a sample of the high-level concepts and these come before hitting the jargon barriers of the implementing technologies. For example, if Kafka is the Message Bus then we have Topics, Partitions, Consumers, Producers, Streams, Compaction, Retention, Exactly Once Semantics (EOS)… the list goes on.

By its nature, EDA has quite a lot to say about the interactions between systems. In any organisation that has different teams looking after different systems, engineers have a lot to learn before they can even begin having high-level conversations about the technical merits of EDA. Despite being a relatively old concept the patterns of Event Driven Architecture are not well-understood when compared to, for instance, a Micro-Services Architecture. Management and business stakeholders understand REST APIs and microservices - these have the honour of being inaugurated into the business and managerial lexicon. EDA does not.

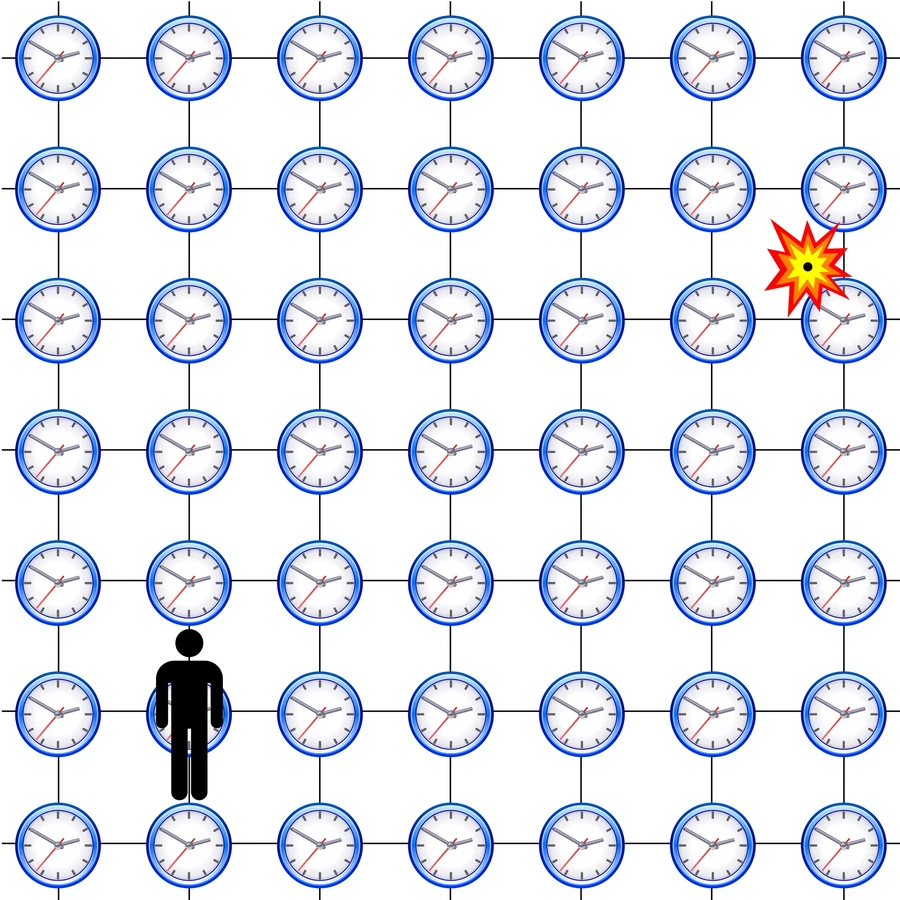

Often a whole-platform event-driven approach is chosen (and mandated) by system architects, which starts a program of work to “Eventify” an organisation’s technical estate. Without a coordinated program of education for both engineers and managers, it’s hard to succeed. All too often the result is endless bike-shedding between teams over terminology, semantics, and philosophy.

Greenfield EDA projects have a better chance of success simply because they don’t have to deal with the baggage of existing systems. However, they have their problems. Excitable engineers, prone to over-engineering and going all-in on a technology stack, may, for instance, eschew the benefits of a traditional database in favour of in-memory state stores rebuilt from event logs at every startup. Before you know it, teams have implemented their own RDBMS.

Over this blog post series, we’ll examine the high-level concepts from the perspective of both engineers and managers and illustrate using Clojure. The first post highlights where people and organisations typically differ in understanding and implementation (as they currently do, and inevitably will in the future).